A history of remembrance

By Zach Hagadone

Reader Staff

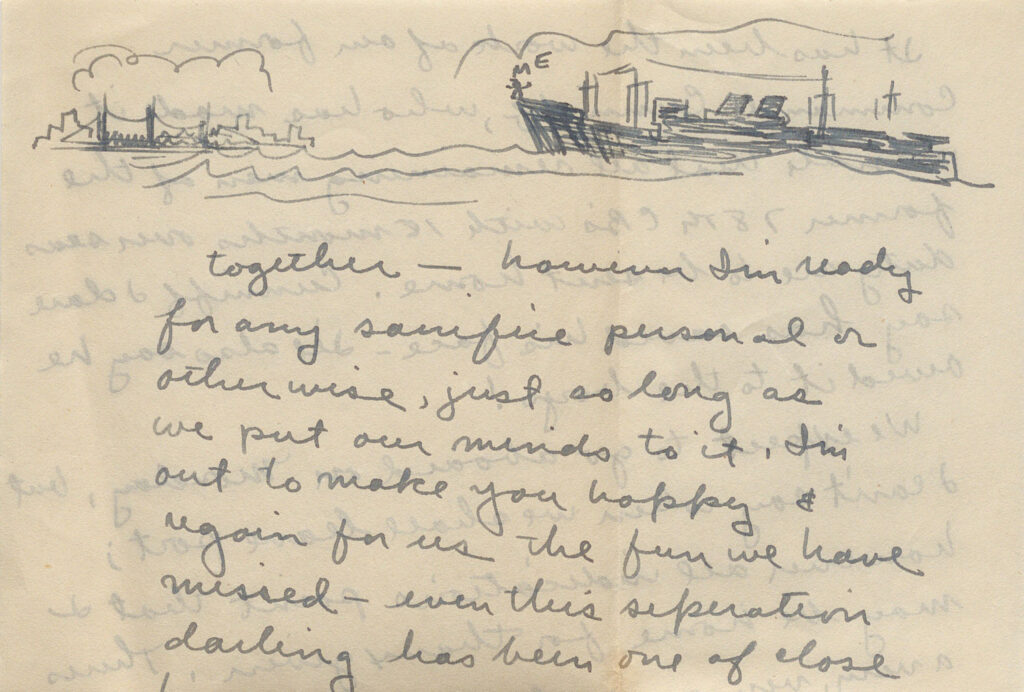

Among the most interesting historical sources are the messages soldiers send home from the battlefront. Not so much for what they tell us about the specifics of warfare, but for how they remain essentially the same, despite being separated by enormous spans of time.

Memorial Day is about remembrance, and the act of being remembered — along with the feelings of homesickness it produces — has always been top of mind for soldiers. Take for instance the letters of Aurelius Polion, a volunteer Roman legionary who served sometime in the 220s CE.

Originally from Egypt, Polion was posted on the present-day border between Hungary and Austria. Other Roman letters dating to the first century CE, and from as far afield as the British frontier, show that legionaries routinely received care packages from their families, but Polion apparently hadn’t received so much as a line or two of communication from his loved ones. Though predating our time by 1,800 years, his homesickness and hurt at not hearing from them is timeless.

“I pray that you are in good health night and day, and I always make obeisance before all the gods on your behalf,” Polion wrote to his mother. “I do not cease writing to you, but you do not have me in mind. But I do my part writing to you always and do not cease bearing you [in mind] and having you in my heart. But you never wrote to me concerning your health, how you are doing. I am worried about you because although you received letters from me often, you never wrote back to me so that I may know how you [are].”

Polion also chastised his other relatives for their silence — especially as he was stationed so far away.

“I sent six letters to you,” he wrote. “The moment you have me in mind, I shall obtain leave from the consular, and I shall come to you so that you may know that I am your brother.”

Then there are the letters — inscribed on bamboo slips — written by soldiers guarding the Silk Road during a period of the Han Dynasty in China from 138 to 119 BCE. Though separated from their Egyptian-born Roman counterpart Polion by about 350 years (not to mention a continent and an empire), they were similarly preoccupied with connecting with the folks back home.

“The prefecture officials sympathize with the ordinary people like us, from the poor families who have long lived outside the Great Wall and new garrison troops are scheduled to replace us,” one message states. “We are waiting to be replaced. When the replacement arrives, we will be able to go back home.”

Another military man stationed far from home complained that terms of service had been unfairly extended, causing distress among soldiers’ family members: “Their parents are worried and their weives sigh day and night.”

To his parents and siblings, one young garrison trooper lamented that his duties would keep him from reuniting with his loved ones.

“The weather is severely cold, and I hope you take care,” he wrote, later adding to his older brother and sister-in-law, “I regret that I am unable to take care of our parents. Thank you for taking care of them. Please accept my deep gratitude.”

Even as far back as the mid-17th century BCE, the mood of soldiers was clearly of great concern to their commanders. As one general named Bahdi-Addu wrote to his king (Zimri-Lim) upon the arrival of a group of troops in Babylon sometime between 1766-1764 BCE:

“By the way, in all expeditions which I have observed there was much griping. Now, in this expedition, I have been watching for it, and there is no griping, none whatsoever.”

Bahdi-Addu’s cheerful troops clearly hadn’t had a chance to get homesick yet. However, based on his past experience (and as experience would teach almost 3,800 years’ worth of future warriors), you can bet the general was expecting some “griping” sooner than later.

Coming up this week! Don’t miss Live Music, the Summer Sampler, the Art Party, Monarch Grind, the Sandpoint Renaissance Faire, and more! See the full list of events in the

Coming up this week! Don’t miss Live Music, the Summer Sampler, the Art Party, Monarch Grind, the Sandpoint Renaissance Faire, and more! See the full list of events in the