Slug Tales From Zone 6: Understanding garden soil

By Soncirey Mitchell

Reader Staff

Dirt is dirt — or is it? Anyone who’s tried to garden in North Idaho knows that our soil varies from bad to worse in most areas. My yard is all rock and hydrophobic silt, and so I’ve had to amend it or build raised beds to grow anything. If you’re serious about planting in Idaho’s native soil, understanding your soil type and contents is a crucial first step that will keep you from planting hundreds of dollars just to watch everything wither.

The clump test

Go to the spot you’ve been coveting for your zucchini or rose bush and dig down at least six inches. This is really the first test — if you can’t dig the hole, the ground is too hard or rocky to grow much. If that’s the case, you’re going to have to consider raised beds or trucking in tons of new soil and mixing it into your land, likely with heavy machinery.

With the hole dug, grab a handful of the dirt and squeeze it like you’re making a snowball with one hand. Hold onto it for five seconds, then open your fist and see what happens. If you have soil like mine, the ball will crumble into a gritty pile because it has too much sand and/or silt. This soil type doesn’t retain water and so will allow both moisture and nutrients to slip away before your plants’ roots can absorb them.

If, on the other hand, you release your grip and the dirt perfectly retains its shape like a handful of Play-Doh, the soil has too much clay. This type of soil has difficulty draining and will, therefore, trap the roots in water, causing them to rot. If your soil has too much sand or clay, the solution is to add boatloads of organic matter like compost and aged manure, which retain the water and oxygen needed for healthy roots.

Loam is the ideal soil for most gardens and is a mixture of sand, clay and silt. When squeezed using the clump test, it will hold its shape in a loose ball but crumble into nice chunks, or aggregates, when disturbed.

The clump test will tell you a lot about your soil’s water retention, but to fully understand it, you can make a DIY percolation — or perk — test. Increase the size of the original hole (see above) to about a foot deep and four inches wide. Fill the hole with water and let it drain; once the water is gone but the soil is saturated, refill the hole with more water and measure its depth. Wait 15 minutes and then measure again. Take the difference between the two measurements and multiply it by four to calculate the drainage per hour.

One to three inches per hour indicates good drainage suitable for most plants. Slow- and quick-draining soil should be amended with organic matter or planted with species and cultivars that prefer soggy or dry soil.

Macronutrients

In addition to a loose texture and good water retention, gardening soil should have an abundance of the macronutrients nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium or potash (K), all of which are necessary for plant growth and health.

Nitrogen is responsible for stem and leaf growth; phosphorus promotes root, flower and fruit growth; and potash keeps the whole plant healthy.

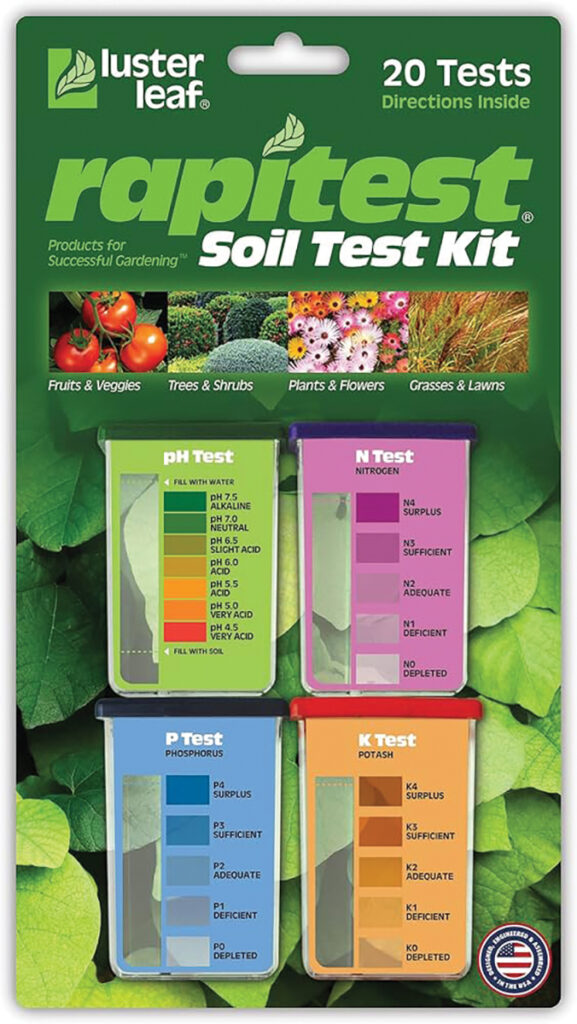

To test for these, you can purchase a simple Luster Leaf rapid test kit from any garden store and follow the instructions on the packet. The test will have four boxes — three for the macronutrients and one for acidity (pH).

Most edible plants prefer slightly acidic to basic soil with a pH level of anywhere from 6.0 to 7.0. To make soil more acidic, gardeners add sulfur or other sulfates. To make it more basic, they add lime (the mineral, not the fruit). Without the correct acidity, plants cannot absorb the nutrients needed to survive.

Fertilizers replenish the soil’s macronutrients and can cater to different deficiencies depending on the NPK ratio. All commercially available fertilizers list a three-number ratio representing nitrogen, phosphorus and potash, in that order. So, for instance, a 20-10-10 fertilizer has two times the amount of nitrogen as it does phosphorus and potash.

Do not add fertilizer to soil that already has acceptable nutrient levels. Excess will not benefit the plants. The nutrients that aren’t taken up by the plants’ roots will wash away into nearby streams and rivers, eventually ending up in the lake and contributing to algae blooms that kill native species. Save the fish and your wallet by testing before you reach for the Miracle-Gro.

Coming up this week! Don’t miss Live Music, the Summer Sampler, the Art Party, Monarch Grind, the Sandpoint Renaissance Faire, and more! See the full list of events in the

Coming up this week! Don’t miss Live Music, the Summer Sampler, the Art Party, Monarch Grind, the Sandpoint Renaissance Faire, and more! See the full list of events in the